Local Leader Spotlight

Love, Consistency, Authenticity, and Faith: Lessons from a City of Newark Community Organizer

By Nakeefa Cilicia Bernard

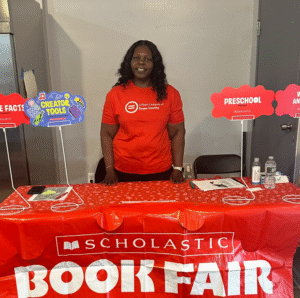

This Local Leader spotlight features lifelong Newark resident, Ms. Katina Leake, a woman of faith, homeowner, and community organizer. She serves in an official capacity as theCommunity Organizer with the Urban League of Essex County. My interview with Ms. Leake revealed a life of commitment to community and compassion for humanity beyond her 9-to-5 in Newark’s Fairmount neighborhood.

Katina is a member of the Fairmount Heights Neighborhood Association, a Parents Unified for Local School Education (PULSE) Legacy Leader, the Chairperson of the Fairmount Heights Children’s Park committee, a thirty-five year-long member of Deliverance Jesus is Coming Church in Irvington, NJ, and in addition to building her own home with Habitat for Humanity in 2010, she has helped to build homes for four other families in Newark. My Zoom interview with Ms. Leake felt like a conversation with an old friend; she told stories and reflected on her experiences in a way that highlighted lessons important to the work of organizing and community building in Newark. Those lessons are to show up consistently and authentically, have faith in people, and love on each other.

On authenticity and consistency

Authenticity and consistency are two different principles, but according to Katina, one would mean nothing without the other in organizing, so the emphasis on both as a package is important to this lesson.

Nakeefa: What’s one lesson you’ve learned from working closely with the community?

Katina: Consistency in this work. Staying connected and being real with the people. Children and adults, if they don’t feel compassion or empathy coming from you, they will not be welcoming of you. Gaining trust means being consistent with my connection with the community. Wanting them to know that I’m here for them in a real, authentic way.

Her authenticity and consistency have proven a successful strategy amidst her multiple community roles. She shared a story about how her authenticity and consistency helped her manage her multiple roles in the community. Public safety is one of her passions, and for two years, Katina worked as a corrections officer in law enforcement. Living in her neighborhood, she began to encounter people she had helped jail, who had served their time and returned to society. “I said to them, ‘SURPRISE, I live here now!’ And the drug dealers and others knew I built a home here, and they developed respect for me because they knew I was invested here.”

On having faith in people

Having faith in people came up in the conversation as we discussed some of the challenges of community organizing. One of the projects that the Urban League is working on is the creation of a new literacy center on South Orange Avenue in Newark’s West Ward. While the physical structure is being built, Katina and the team at the Urban League are simultaneously conducting outreach to the community so that children and families who need the Center’s services are aware of the forthcoming programs. She describes how having hope and faith in people is crucial for combating the challenges of recruiting and keeping individuals engaged in quality-of-life programming.

Nakeefa: What are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced in your work?

Katina: Some challenges are that some of our people are not receptive about welcoming change. When we promote literacy, we find that some of our parents may also be illiterate and may need help as well. So, if our older generation needs the services we are offering to the youth, this can be a pushback or a defense. The pushback of offering services, setting appointments, and when it comes time for them to show up, they may not show up. When it comes to literacy, growing homeownership, just encouraging them to be part of it, you lose folks. Drugs, homelessness, mental illness—these are challenges in the community…but still understanding and realizing that these people are people too, and we still have to love on them and offer resources in hopes that their lives can change.

Love on each other

During the interview, Katina repeatedly used the phrase “love on each other”. Her idea of loving on a person extended beyond the colloquial urban adage of “showing love”. In Katina’s discussions of loving on a person, she was describing a type of love that was resolute, a love to be shared without condition, without qualification. “This work has its pluses and minuses. It teaches you empathy. Some people might smell or look a certain way, but God gives you that empathy to love on people no matter how they look or smell, to help them.” She also added, “I’m here to organize and outreach and bring my community together by way of loving on each other, providing healing spaces to grow our community…I consider myself the bridge that closes the gap by providing the community with literature and invitations to programs and services…to grow in different areas of their life, to help them become economically successful.”

To Katina, love, consistency, authenticity, and faith are key ingredients to the community organizing recipe. “The work is not easy. The work takes faith. It takes courage. It takes prayer. To grow it, to connect, and make sure that what you’re doing/setting out to do, isn’t falling on deaf ears or on stony ground.” According to Katina, having faith in community members and being brave to show up for them authentically, consistently, and with love, is her approach to overcoming the challenges of community building in Newark.

In my last question, I asked Katina what is one thing you’d encourage residents or local leaders to do to help build a stronger, healthier Fairmount? She replied, “Get involved and stay involved! Offer your time; if it’s one hour a day or three hours a weekend. Get involved in the happenings that’s taking place for the communities to grow. Don’t expect 1 or 2 people to hold down the fort. When you see a movement taking place, join, volunteer, share to connect and grow what’s taking place.”

If you are interested in getting involved, need support, or would like more information about the Urban League of Essex County’s new Literacy Center, please contact Katina by email at kleake@ulec.org or by phone at 973-951-6355.